South, East and Southeast Asia

300 BCE-1980 CE

TOPIC 8.3 Interactions Within and Across Cultures in South, East, and Southeast Asian Art

Trade greatly affected the development of Asian cultures and Asian art. Two major methods for international trade connected Asia. One was the Silk Route that linked Europe and Asia, connecting the Indian subcontinent to overland trade routes through Central Asia, terminating in X’ian, China. The second was the vast maritime networks that utilized seasonal monsoon winds to move trade among North Africa, West Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and south China. These routes were the vital mechanism for the transmission of cultural ideas and practices, such as Buddhism, and of artistic forms, media, and styles across mainland and maritime Asia.

Religion and Culture

Buddhism was actively imported to Japan from Korea and China in the 7th and 8th centuries. It succeeded first in China, and then other countries, because of courtly patronage and similarities with local traditions.

South, East, and Southeast Asia were also home to foreign cultures and religions, including GrecoRoman cultures, Christianity, and most notably Islamic cultures from West and Central Asia. Islamic influence is particularly strong in India, Malaysia, and Indonesia, which were under at least partial control of Islamic sultanates during the second millennia CE. These regions have also been influenced by cultures and beliefs from West Asia and Europe. Today South and Southeast Asia are home to the world’s largest Muslim populations.

(8) 195. Buddha at Longmen Caves.

Chinese (Sui, Tang, Song). 493-1127 CE. Chinese.

© CLARO CORTES IV/Reuters/Corbis

Learning Objective: Chinese Buddhist sculpture

Themes:

Politics

Propaganda

Religion

Place of worship

Rulers

Buddha at Longmen Caves is located at Longmen Caves, in Luoyang, China. Made from hard, gray limestone the largest Buddha measures 57 feet. These were carved in situ into living rock as high relief. Here there are 2,300 caves and niches that extends for over a mile.

The Buddha and bodhisattvas display a new, softer, and rounder modeling, as well as facial expressions. Vajrapani and lokapala display a more engaging and animated musculature, with forceful poses. These would have been painted in brilliant blues, reds, browns, and golds.

Why this was Created

This is a place of Buddhist worship.

The patrons were emperors (and one empress) and this was the display of power and piety of these people. Rulers wielded Buddhism to affirm their piety, superiority, and tolerance. Specifically, this revealed the strength and spirituality of Tang Dynasty. It was a metaphor for political power.

This arrangement with Buddha in the center emphasized a correct religious order.

© Christian Kober/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis

Similarly, the Tang Dynasty was struggling to balance bureaucrats and aristocrats, who consistently posed a threat to the emperors. For emperors to sponsor productions of artworks such as these was to show that there was a likeness between the emperors and Buddha. Thus, aristocrats and bureaucrats should be subservient to the emperor, just as bodhisattvas and disciples were to Buddha.

This sculptural arrangement intentionally mirrored the political situation – one person is supreme.

Used by Permission

Content

Buddha at Longmen Caves contains in total almost 110,000 Buddhist stone statues, more than 60 stupas, and 2800 inscriptions.

A Look at Fengxian Cave

The specific cave we are examining is called Fengxian Cave. Here 9 figures pose as a group.

From Left to right:

- Vajrapani

- Lokapala

- Bodhisattva

- Disciple

- Vairocana Buddha (Buddha who represents all the infinite wisdom in the universe),

- Disciple

- Bodhisattva

- Lokapala

- Vajrapani

A bodhisattva are Buddhists who do not pass on to nirvana, but who stays to help.

Vajrapani are Chinese guardians of Buddha, who wields thunderbolts. The violence is justified only if there is a threat made to Buddha.

Lokapala are heavenly kings who watch over one of each of the cardinal directions.

There are many smaller figures of deities, monks, and donors surrounding the nine main figures.

Context

Most of the carvings date between the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 8th century (Northern Wei through early Tang). Wei had moved capital to Luoyang in 494 CE.

Tang Dynasty was considered the age of Buddhism in China

- Buddhism and Confucianism each vied for power over emperors.

- Many Chinese, Indian, Central Asian, and Southeast Asian monks traveled through Asia, spreading Buddhism’s messages.

- Alternating periods of Chinese Buddhism’s popularity or lack thereof prevented constant flow of work.

- Largest period of construction (and the construction of Fengxian Caves) was sponsored by Emperor Gaozong, and his wife and the one and only empress of China, Empress Wu.

(8) 198. Borobudur Temple

Sailendra Dynasty. c. 750–842 centuries

Borobudur Temple, in Central Java, Indonesia, is made from volcanic-stone masonry. It is the largest Buddhist temple in the world and ranks with Bagan in Myanmar and Angkor Wat in Cambodia as one of the great archeological sites of Southeast Asia.

Borobudur Temple is 300 years older than Angkor Wat and 400 years older than the European Cathedrals. The Indonesian temple was buried under volcanic ash and overgrown with vegetation until discovered by the English lieutenant governor Thomas Raffles in 1814. A team of Dutch archaeologists restored the site in 1907–11. A second restoration was completed by 1983.

Function

Visiting the temple requires circumambulating through the corridors. It is a ritual that helps Buddhist to understand the Buddha’s teachings, known as the Four Noble Truths (also known as the dharma and the law). This helps to understand samsara, the endless cycle of birth and death.

Climbing up successive terraces allows for understanding the transition from the lowest manifestations of reality, through a series of spiritual regions, toward the enlightenment at the summit which allows unrestricted views of the mountains, offering a liberating feeling of spaciousness.

One enters on the east gate, and reads from left to right, moving in a clockwise direction around the monument. Almost 5 km of carved bas reliefs educate the illiterate according to Mahayana Buddhism texts. These texts deal with the self-discovery and education of the bodhisattva, conceived as being with compassionate, and fully devoted to the salvation of all creatures.

The stories from Buddha’s life, Jataka and Avadana illustrate lessons on morality, karma and merit that distinguished the enlightened creature.

Buddhist religion, philosophy and cosmology is woven into the architecture of the Borobudur. The temple is the symbol of Mount Meru, which is considered the center of the universe in Indian cosmology.

Based on the teachings of Buddha the temple represents:

- the Four Noble Truths

- the Noble Eightfold Path

- the three realms of existence: Kāmadhātu, Rūpadhātu and Arūpadhātu

These help to guide the visitors to follow the spiritual teachings.

Kāmadhātu (Desire Realm)

- 160 reliefs based on the text of Mahakarmavibhangga, which is about the law of cause and effect (karma).

Rūpadhātu (Form Realm)

- Scenes depicting mankind’s consciousness about the meaning of life through reliefs on a four sides gallery, both inside and out.

- To view in the correct order, one must walk around clockwise four times and observe both upper and lower reliefs.

Arūpadhātu (Formless Realm)

- reliefs depicted at the top illustrating Enlightenment (Nirvāṇa) which requires an almost five kilometer walk clockwise, ten times, to view correctly.

Other Forms of Decoration

- birds

- flowers

- mythical beings like Kāla above the temple entrance

- Makara mythical being with an elephant trunk and an open mouth from which the head of a lion emerges are at the base of the gate.

Borobudur Temple is shaped as a stepped grey andesite pyramid with 3 levels—a square base, a middle level of five square terraces, and an upper level of three circular terraces—totaling 9 lesser sections. The number 9 which represents the end of a cycle in the decimal system, which originated from the Indian subcontinent as early as 3000 BC is mystic in Buddhism and Hinduism. Important Buddhist rituals usually involve 9 monks.

The historical Buddha had 9 virtues:

- Accomplished

- Perfectly Enlightened

- Endowed with knowledge and Conduct

- Well-spoken

- the Knower of worlds

- the Guide Unsurpassed of men to be tamed

- the Teacher of gods and men

- Enlightened

- Blessed

The 3 circular terraces carry small stupas, crowned at the centre of the summit by a large, circular, bell-shaped stupa, 115 feet (35 metres) above the base. The bottom plinth encasement that obscures an entire series of reliefs consists of a massive heap of stone pressed up against the original structure. It was probably added to hold together the bottom story, which began to spread under the pressure of the immense weight of earth and stone accumulated above.

The lowest level, which is partially hidden, contains reliefs of earthly desires, illustrating “the realm of feelings/desires”, the lowest sphere of the Mahayana Buddhist universe. It portrays the law of cause and effect. For example, if you like gossiping, you might be reborn with an ugly appearance.

The next level is a 13-foot-wide corridor open to the sky and adorned with bas-reliefs that depict “the realm of forms” through events in the life of the historical Buddha and scenes from the Jatakas. There are 2 registers: the balustrade depicting fables about altruism.

Opposite the balustrade is the main wall where the Jatakas stories are located.

Lalitavistara, a set of 120 reliefs on the first platform, depict Prince Siddharta’s life from birth to enlightenment.

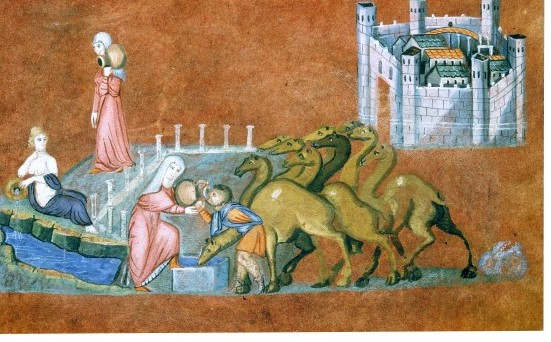

Queen Maya riding in a horse carriage is retreating to Lumbini garden to give birth to Prince Siddhartha. In the nativity scene, Queen Maya’s depiction recalls the tree spirits or yakshinis. These spirits are are often shown as beautiful and voluptuous, with a flywhisk in right hand, fleshy cheeks, wide hips, narrow waists, broad shoulders, knotted hair and exaggerated, spherical breasts. According to legend, the infant stood and took seven steps. With each step, a lotus flower appeared, to prevent his tiny feet from touching the ground.

Here is the Story

“Prince Siddharta was born to King Sudhodana and Queen Maya of the Sakya clan who reigned in Kosala, India, around the fifth century BC. One day Queen Maya had a dream of a white elephant entering her womb. This dream was interpreted by priests as a sign that the couple would bear a son, who would become either a world ruler or a Buddha. The king preferred him to be the world ruler, so he confined the prince in the palace and indulged him in sensual pleasures.

As fate had it, one day the prince went out of his palace and he saw a sick person, an old person, a corpse, and a monk. Siddharta realized that he, too, would become old, sick, and die. Later, he renounced his mundane life and embarked on his search for true happiness. After learning from several spiritual teachers, and practicing severe ascetism for six years, he finally meditated under a bodhi tree. Here he attained enlightenment. Because of his compassion for fellow humans, he revealed the path to achieve unconditional happiness.”

The Jataka tales are about the 500 Bodhisattvas, the alternating human and animal forms in which Buddha was reincarnated before he was born as Prince Siddhartha and attained enlightenment.

Animals perform self-sacrifices for other beings. “A sad monkey hugging a buffalo’s neck is the story of real friendship. One day a monkey had a problem. An ogre wanted to eat him. Devastated, the monkey told his buffalo friend about his fate. The buffalo comforted the monkey, saying that he would offer himself instead. What’s more, the buffalo’s body was bigger. The buffalo just asked themonkey to send his best wishes to his relatives. Then they both met the ogre. Touched by thekindness of the buffalo, the ogre dismissed his plan to eat either of them.”

- Avadana (Noble Deeds) are similar to Jataka, but the main figures are legendary people.

Sudhana’s quest for enlightenment

He was an Indian youth, maybe a merchant’s son seeking bodhi (enlightenment). He takes a pilgrimage on his quest for enlightenment and studies under 52 “teachers”: a doctor teaches him compassion for the ill, children playing teach him about simple happiness,…

Detachment from the Physical World

The upper level illustrates “the realm of formlessness,” or detachment from the physical world. There is little decoration, but lining the terraces are 72 bell-shaped stupas, many containing a statue of the Buddha, partly visible through the lattice stonework. The 504 Buddha statues are shaped to express 6 different mudras (hand positions).

Buddha Hand Gestures and Significance

- Right hand across right knee symbolizing the summons of the Earth Goddess.

- Right hand open with the face of the hand facing upwards – a symbolic gesture of loving kindness by the act of giving.

- Both hands folded on his lap symbolic for meditation.

- Right hand raised upwards with the face of the hand facing the audience – a symbolic gesture of dispelling of fear.

- Right hand slightly lifted upwards with the tips of his thumb and index finger touching each other – a symbolic gesture of preaching the Dharma.

- Both hands raised in front of the center of the upper body, touching with his right ring finger his left index finger – by far the most important symbolic gesture, for it represents the turning of the wheel of the Dharma.

- The archways allow people to access the higher levels are decorated with pre-Buddhist elements, such as the fearsome face and open mouth of Kala. This is a Hindu deity from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, In Javanese mythology, Batara. Kala is the god of destruction.

Symbolism of the Mandala

The temple’s plan suggests a mandala, one of the richest visual objects in Buddhism. A mandala is a symbolic picture of the universe painted on a wall or scroll, or simply created with colored sands on a table. It represents an imaginary palace that is contemplated during meditation. Each object in the palace has significance, representing an aspect of wisdom or reminding the meditator of a guiding principle.

The mandala’s purpose is to help transform ordinary minds into enlightened ones and to assist with healing. The entire sacred manmade mountain of chiseled gray andesite is a giant stupa. On the topmost terrace, the main stupa contained an unfinished image of Buddha with the hands not fully carved that was hidden from the spectator’s view, symbolized the indefinable ultimate spiritual state.

Techniques

Progressively the reliefs on the terraces become more static. The sensuous roundness of the forms of the figures is not abated but, in the design, great emphasis is laid upon horizontals and verticals and upon static, formal enclosures of repeated figures and gestures. At the summit all movement disappears.

The circular design enclosing the stupa, between the reliefs are decorative scroll panels, and a hundred monster-head waterspouts carrying off the tropical rainwater.

The stone was cut to size, transported to the site and laid without mortar.

The Javanese Variation

Although the origin of the temple is based on Indian mythology and Buddhist iconography, one can see the Javanese influence. The statues are less refined and have been recreated in the local perception of beauty. This is the way Buddhism was manifested in Java during the Sailendra dynasty.

Based on Indian influences and Mahāyāna Buddhism, arriving via China during Tang dynasty (618-906), this became the Buddhism of Java.

Sailendra dynasty shared their power with the Hindu dynasty Sanjaya. For example, the construction of the Kalasan temple – illustrates, that, apart from its religious function, the Borobudur also formed an important expression of power.

Tradition

The congregational worship in Borobudur is performed in a walking pilgrimage paying reverence to the stupa. This is achieved by circumambulating and keeping it on the right. The visitor is transformed and educated, while climbing through the levels of Borobudur. The encountering of illustrations of progressively more profound tales from Jataka and Avadana is achieved in a similar way to the very early frescoes of the Ajanta Caves in India.

Pilgrims are guided by the system of staircases and corridors ascending to the top platform. Each platform represents one stage of enlightenment. The path that guides pilgrims was designed to symbolize Buddhist cosmology.

Vesak, the “Buddha Day” ceremony, occurs once a year during a full moon. thousands of Buddhist monks walk in solemn procession to Borobudur to commemorate the Buddha’s birth, death, and enlightenment. Devotees may bring simple offerings of flowers, candles and joss-sticks to lay at the feet of their teacher.

(8) 199. Angkor, the temple of Angkor Wat, and the city of Angkor Thom, Cambodia

Angkor Dynasty, Hindu – c. 800-1400 CE

Learning Objective: Hindu/Buddhist temple

Themes:

Architecture

Place of worship

Appropriation

Deities

Politics

Power

Rulers

Propaganda

Water

Funerary

Good vs evil

Religion

Angkor Wat, in Siem Reap, Cambodia is the largest religious monument in the world. It was built for the patron King Suryavarman II (1113–1145/50 C.E.) and dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu, one of the three principal gods in the Hindu pantheon, along with Shiva and Brahma. Vishnu is known as the protector.

It is believed that Angkor Wat was also to house the king after death and used as a mausoleum.

The name Angkor Wat comes from the Khmer language, the official language of Cambodia. It means City Temple.

Siem Reap was once the capital of the Khmer empire, then known as Angkor. From the 800s to the 1300s it was a prosperous hydraulic facility that collected monsoon waters from the rainy season, in huge basins. This elevated flooding, and protected plantations during drought.

Merchants and traders of gold and spices brought Hinduism and later Buddhism. Business opportunities caused people to stay in the region

Since Angkor itself was the technical source of the life-giving agricultural water controlled by the king, it was regarded by the Khmer with religious reverence. Its temples and palaces were an expression of that and at the same time an essential part of its supernatural mechanism.

Royal intercession by numerous ceremonies, some of which re-enacted the primal marriage of Hindu divinity and native earth spirit on the pattern of ancient folk cult, ensured the continuing gift of the waters of heaven.

The king, an earthly image of his god, was the intermediary who ensured that his kingdom would continue to receive divine benevolence in the form of water in controlled quantities.

Courtiers played roles both religious and administrative for the king, who believed that after his death he would be united with his patron deity. Dedicatory statues were often set up in his chief temple to commemorate his divinization.

The Khmer kings were tied to the city, even as they changed religions. The city was transformed using both Hindi and Mahayana Buddhist architecture and artistic style layers beneath the surface of the temple.

Content

A large moat and a high wall surround Angkor Wat on all sides, which are longer than one kilometer.

Inside the temple develops on three levels:

- a new enclosure, formed of galleries, pierced with monumental porches on all four sides and provided with corner towers

- a second floor repeating the same arrangement

- a central tower composed of five towers-sanctuaries staggered and interconnected by cruciform galleries

The temple mountain was a Southeast Asian invention in architecture. It represented a union between the gods and the reigning king. The capital, a square measuring 4 kilometers on each side was lined with a double rise of land. Here two axial avenues crossed ending in a natural hill in the center.

The five stone towers symbolized the five mountain ranges of Mt. Meru, the mythical home of Hindu and Buddhist gods. It was also considered an axis-mundi or a world axis that connects heaven and earth.

In his city, the king could intercede and re-enact the marriage of the Hindu divinity and the earth spirit to ensure the continuing gift of waters from the heaven

Inspiration

The temples continued to multiple, with each sovereign trying to outdo the next. The small temple of Banteay Srei, built in 967, is located 20 kilometers north-east of Angkor. It is surrounded by a low-rise enclosure that is pierced by entrance pavilions and bordered by a moat. With three towers consisting of pink sandstone, this is the first temple to use relief sculptures to illustrate Indian legends. This is a prelude to classical Khumer style. Note the reliefs of devatas (gods of Hindu epics such as Ramayana and the Mahabharata) and the tympanums depicting Hindu myths, such as the rain of Indra.

Rich in Decoration

At Angkor Wat over a thousand dancing apsaras (female spirit of the clouds and waters in Hindu and Buddhist culture) unfold on the walls of the different courts and on the pilasters. Dressed in a bell skirt from which are two large pieces of cloth at the waist, they are lavishly adorned with bracelets, armbands, necklaces and earrings, and extravagant hairstyles.

A Closer Look at Bas-Relief Sculptures

The greatest achievement of the Angkor Wat sculptors has been reached in the tens of meters long bas-reliefs of the galleries of the second such as the Churning of the Sea of Milk or Heavens and Hells.

Heavens and Hells

- marked contrast between elected and damned

- dramatic groupings

Churning of the Ocean of Milk

- move from a low precise relief to a light background relief.

- composition is willingly monotonous

- opposing alignments of gods and demons, which pull on the Naga (serpent king) as if they play a tug-of-war game, the Churning of the Sea of Milk.

The Myth

The Churning of the Milk is a Hindu myth about the eternal struggle between the forces of good and evil, as well as light and darkness. Due to this struggle twelve precious things are lost in the ocean.

The god Vishnu thought to use the holy mountain Mt. Mandara as a churning stick, surrounded by the serpent king (naga). This was tugged between the demons and the gods. They pulled with all their might! The churning stick stirred the waters of the milky sea for 1000 years— before recovering the amrita, the elixir of eternal life. The foam from the churning produces apsaras, who appear on both sides of Vishnu. Once the elixir was released, the supreme god of the Vedes, Indra descended to catch it and to save the world from the demons.

The Rise of Jayavarman VII

© HansStieglitz@t-online.de

After the death of Suryavarman II, the Champa (the people of nowadays Vietnam) occupied the Khmer kingdom for four years (1145 to 1149).

Jayavarman VII achieved the following:

- liberated his country and restored order.

- conquered Champa (Vietnam), Laos, Thailand and Burma achieving the maximum extent of the Khmer kingdom

- enthroned in 1181

- reorganized the Khmer country

- built a road network linking the provinces to the capital and lined them with lodgings for travelers

- built hospitals

- changed his religion switching from the defeated Vishnu to Buddhism (Mahāyāna).

- raised temples dedicated to the worship of his parents

- 1186, that of Ta Prohm, in Angkor itself, dedicated to his mother deified under the aspect of a female counterpart bodhisattva.

- 1191, the temple of Preah Khan of Angkor, in memory of his father in the aspect of Bodhisattva “Lord of the World”.

A Work in Progress

Simultaneously, he had to restore Angkor Thom the capital itself, destroyed and pillaged by the Chams. It used to be centered on the Baphuon, which was more than a hundred years old. Jayavarman VII recentered it on a new temple-mountain, the Bayon and surrounded it by a moat and a high wall of stone. The new city, Angkor Thom, was – like the previous ones – enclosed in a vast quadrilateral, each side of which was oriented in relation to a cardinal point. Four triumphal ways (north-south and east-west) cut it into quarters.

The Buddhist cosmology inspired the symbolism and dispositions of the great foundations (Angkor Thom, Preah Khan, etc.). The architecture (plans and elevations of the temples, construction processes) and sculpture (iconography, aesthetics, adjustments) of the style of the center of its new capital, Bàyon break with four centuries of stylistic evolution and mark its end.

The Plan

Construction was not random. By combining Brahmanic notions and Buddhist ideas the architectural purpose was the glorification of the king, his deification, and his identification with the empire. Jayavarman VII, converted to Buddhism, found satisfactory solutions present the capital as the center of the world of the gods, where the king lived as equal of the gods and the protector of the world.

- moats were oceans that encircled the world, enclosing the mountain ranges that border it

- doors, surmounted by towers adorned with the deified face repeated four times, facing each cardinal point

- gave access to roads lined on both sides of a hundred and eight giants of stone holding a colossal naga

- theme of churning of the ocean, myth of creation, and that of the rainbow unites heaven and earth.

- In the center, the Bayon, symbolic temple-mountain with a circular interior and radiant reminiscent of the Buddhist stupas, provided 50 faces, with the “smile of Angkor”, which one finds the echo in the countless statuary of this time.

Angkor Wat as a Mandala

A mandala or circle in Sanskirt, is a spiritual geometric configuration of temples in Buddhism. This allows for harmony with the universe by aligning with the planets, sunrise, and sunset. Angkor’s central axis through the temple’s main tower, aligns with the morning sun of the Spring Equinox.

Destruction, Change and Abandonment

In 1234, Jayavaram VIII, who succeeded two Buddhist Kings, destroyed Angkor and all effigies of Buddha. He was an iconoclast operating at a very large scale. In total tens of thousands of Buddha images were defaced.

At the end of the 13th century, the definitive adoption of Theravāda Buddhism led to a radical change in architectural traditions and ended all major construction programs. Advocating a simpler way of life, the Theravada Buddhism made Angkor Wat the Buddhist center of the kingdom.

Around 1431 a new Thai attack destroyed the hydraulic system on which the economy of the kingdom was based. Shortly after, the royal court abandoned Angkor.

(8) 208. Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings.

Bichitr. 1620 CE. Islamic.

© Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C

Learning Objective: Islamic miniature

Themes:

Rulers

Text and image

Propaganda

Cross-cultural

Power

Politics

Religion

Commemoration

Museum: Smithsonian (Freer Gallery of Art)

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings is also known as Jahangir Enthroned on an Hourglass. This work on paper, by artist Bichitra is comprised of watercolor, gold and ink and measures 10 inches tall.

It is one of the symbolic paintings of Jahangir’s reign, eulogizing the power status of the contemporary dynasty. One of the many novel expression methods, the symbolism is distinctly handled.

To view you must concentrate on the aesthetics of composition, color palette, and a manipulative variation of figural sizes.

Bichitra, the painter, depicted various vegetal forms along with the calligraphic verses on the border. This trademark work combining many regional influences, illustrates Bichitra’s use of cross-cultural motifs to convey Mughal principles. Jahangir accepted European entry into the Indian subcontinent, which brought in western motifs in Indian art. This included Mughal miniatures are a part of larger books.

The thick and colorful floral border on the painting defines the Jahangir-era of Mughal art. The folio, as part of Muraqqa, establishes the spiritual trait of Jahangir’s personality by portraying the Sufi Sheikh as a prior figure after himself.

The Main Characters

The painting comprises five human figures of a reputed status, in decreasing order of visual size. The largest figure is that of King Jahangir, while the man in front of him is Sufi Sheikh Hussain, in a dimension little shorter than him. The king is adorned with jewelry as opposed to pale garb of the sheikh.

King Jahangir is handing over a book to the Sufi Sheikh Hussain, which he accepts in a shawl, avoiding the physical contact, as an imperial protocol.

The figure below the spiritual leader is an Ottoman sultan, followed by English King James I. Ottoman sultan’s turban-tied headdress distinguishes him as a foreigner to the Mughal court, while he awaits his chance to greet Jahangir. King James I, in his royal attire, gazes out of the painting, which is a typical style of European art.

The last figure is that of the artist himself, Bichitra. Despite the significance over the form of the King’s figure, the ochre-chrome yellow garb of Bichitra grabs the attention compulsively. However, the attire’s fashion indicates that he was a Hindu artist in the Mughal court. He is holding a miniature painting, which suggests his profession.

Adaptations of European Forms

Apart from these, the other flying semi-human forms are putti figures, which are European-influenced characters.

The halo behind the Jahangir’s head, and hourglass, are further adaptations of European forms. Concentric in kind, glaring flames around the head seemingly recognize his sun-like illuminated and authoritative demeanor.

At the same time, the crescent moon at the lower arc of the halo is a prevalent representation of spiritual enlightenment in Jain paintings. Symbolically, the crescent moon also narrates the endless cycle of day and night.

King Jahangir is seated on a large and ornate hourglass. On the putti on the hourglass are engraving with an inscription that reads, “Allah is great. O Shah may the span of your reign be a thousand years”.

The hourglass is an emblematic attribute of the beginning of the new Islamic millennium, it begins with the rule of a knowledgeable Mughal ruler.

From these forms we can infer that Bichitra had been studying European artworks that were accepted by the king as gifts.

Realism

While figures are naturalistic and convincingly real, space itself is tipped upwards and flattened. A few areas are painted in gradual tonal values, while the rest is in flat application of colors. Artist has utilized a colorful palette with incredibly precise and intricate detailing. Notably, the division of backdrop helps in acquiring a rhythmic gaze over the work.

An ornate lower half, which apparently is a Persianate carpet, is replete with abstract, repetitive, and naturalistic design. In addition, the artist has neglected linear perspective to feature the content significantly.

Frames Within Frames

The painting is enclosed in a group of rectangular frames that show a varying floral and calligraphic designs. Bordering with repetitive and small decorative cartouches, the background of the folio has floral arabesque. These floral motifs are inspired by the local flowers of the region.

At the cusp of the painting, on the vertical edges, the band depicts a calligraphic verse praising the king. The lower band expresses, “Though outwardly Shahs stand before him, he fixes his gaze on dervishes.”

Function

Mughal miniatures were often a part of a more comprehensive book project called Muraqqa. Murraqas describes lives of Mughal kings or elites. They were accessible to the selected and not common men.

After the volume was written, it would be given to an artist with secluded pages to illustrate the relevant narratives.

The purpose of this folio was to render a spiritual and wise image of noble Mughal King Jahangir. As he preferred a spiritual Sufi Sheikh over the kings of the world, he is indicated to be a grand sovereign of the Indian subcontinent.

Mughal paintings are said to have used gold, silver, and lapiz lazuli, among other hues, for rendition. The usage of material depended on the project and the role it played over the larger mass. The colors were generally obtained from local natural resources. For example, white was made by grinding the conch, while black from the lamp residue.

In addition, Mughal kings followed greater political propaganda to disperse the might of the Mughal ruler. It also displayed Jahangir’s legitimacy, piety, and reverence for religious deeds. Proving piety’s fervor over the power, he tended to behave accordingly in terms of the rank of the individual. By staging the king on an hourglass, Bichitra had conceded a much-accepted weight to his honor. In European culture, hourglass projects the existence of calculative time. By enthroning Jahangir over the same, he disposes the ideology to the supremacy of the royal figure.

Traditions

Mughal art and architecture began thriving from the reign of the first Mughal king, Babur (1483 -1530). An Islamic rule, the Mughal kings were known for their opulence and extravagance. Due to regular trade exchange with near-east locations, Mughals generated immense wealth. Hence, they observed a long tenure in the Indian subcontinent, almost encroaching across the entire land.

Babur, the first Mughal ruler, was a patron of arts who descended from the Timurid sultanate. To cultivate Islamic art in India, he brought Persian artists with him. While Indian indigenous art was enriched with many centuries of artistic expertise, the entry of Persian art resulted in the merger of forms.

Nevertheless, after Babur, it was Humayun (1508 -56), his son, who lived in refugee at Shah Tahmasp’s, a Safavid Persian ruler in India, court and had observed many painters at work. Subsequently, he engaged in creating folios and books, which included the famous Hamzanama.

Hamzanama is a book on the life and adventures of Hamza, who was an uncle to Prophet Mohammad. However, with the sudden demise of Humayun, Akbar (1542 – 1605), who was to be one of the great emperors of Mughal India, took the charge of art patronage. As mentioned by court historians, Akbar had hired more than 100 artists and established many ateliers.

Since Akbar, the Mughal kingdom experienced a stable state for the future kings. Jahangir (1569 – 1627), unlike Akbar, was meticulous about the accuracy and anatomical details of the natural forms in the painting. Moreover, allegorical miniature portraits were a popular painting genre among Jahangir’s court painters

Although Europeans had begun negotiation since the Akbar’s reign, Jahangir accepted their desire to trade in the Indian subcontinent. Due to the increase in commerce, the European forms along with Indian and Persian began appearing in the paintings by court painters. Thus, Jahangir era paintings evolved a cross-cultural style, for political and cultural agendas.

Patrons

Bichitra (pronounced Buh-Chit-truh) is the artist to Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings under the patronage of fourth Mughal King Jahangir, son of Akbar.

As mentioned before, Muraqqas were major projects undertaken by ateliers of Mughal kings to record their political and personal life, in some cases. Baburnama, Akbarnama, Tujuk-I- Jahangir, among other publications, are rich examples of the Mughal lineage of biographies. Today these documents present us with detailed data about the kings, elite officials, and political activities of the kingdom.

Establishing ateliers, each Mughal king had been instrumental in sustaining artists and the culture of the regions. Humayun, intending to sustain the nomenclature of Mughal art and architecture, brought two Persian artists named Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd us Samad. The ateliers of Akbar drew many international artists to prosper in their careers.

These ateliers had Hindu artists, too. Incorporating their scholarships, Mughal art experienced a peak period in these centuries. However, post-Shah Jahan’s, Jahangir heir era, the subsequent Mughal rulers did not bestow a keen enthusiasm in art patronage. By the 19th century, Mughal art underwent a severe downfall due to many political factors.

Historical Context

Indian subcontinent had witnessed many tumults of foreign invasion, which eventually affected the artistic and architectural praxis. However, the indigenous form of painting had also evolved, projecting a rich color palette, and flat background in ornate manuscripts. Mughal invasion, however, was to stay for a longer time, and thus it amalgamated many styles that it brought with the existing Indian ones.

During Akbar’s reign, in 1591-2, the Islamic second millennium had commenced. Being aware of solar and lunar events, the Mughals were well versed in astrology and followed the Islamic calendar. When Jahangir accepted the throne in 1605, it was already ten years past the onset of the new millennium. Hence, the hourglass, a typical European collectible, is a definite symbol of the passage of time and positing Jahangir has a messianic king.

About the Artist

Bichitra was one of the revered Hindu painters in the Mughal court. As Jahangir was a proponent of scientific accuracy and detailed approach, Bichitra was deft in his craftsmanship to create wonderful paintings. Moreover, in the case of Bichitra, symbolism and semantic ideas brim his creative compositions. Such paintings have never been attempted before Jahangir’s reign.

(8) 209. Taj Mahal

Mughal. Created under the supervision of Ustad Ahmad Lahori, architect to the empire. 1632-1653 CE. Islamic (Indian).

© David Pearson/Alamy

Learning Objective: Islamic mausoleum

Themes:

Funerary

Text and image

Cross-cultural

Commemoration

Male/female relationships

Architecture

Water

Landscape

Status

Power

Rulers

Taj Mahal in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, in Northern India, is an ancient Indian mausoleum representing exquisite Indo-Islamic architecture that measures 240 feet across and sits on 42 acres. The building is made with stone masonry and marble, along with an inlay of precious and semiprecious stones.

Taj Mahal is an ancient Indian mausoleum representing exquisite Indo-Islamic architecture. Considered as one of the seven man-made wonders of the world, the Taj Mahal is known as the Crown of the Palace. Originally, it was known as Rauza-i-munawwara, which means illuminated tomb.

Projecting unique beauty, the mausoleum is a wondrous home to the couple-tombs of Shah Jahan, a Mughal King and his beloved wife Mumtaj Mahal, the name of which bestows the title to the revered tomb. Comprising calligraphic decoration in precious gemstones, it is an exceptional Mughal structure in white marble. Many kinds of research on the yellowing of the marble have been conducted in light of global warming, resulting in strict restrictions over the surrounding vicinity.

Interestingly, the Taj Mahal is not a singular marvel, rather it is a large complex of twin mosques, exemplary gardens, and marvelous gates. In 1983, UNESCO designated the Taj Mahal and the complex as World Heritage site. A thoughtful blend of Persian, Turkic, and Indian styles, it is one of the finest instances of Mughal art and architecture.

Content

© Ocean/Corbis

The Mughal kingdom had expanded its rule over vast areas of northern and central India. Reigning the Indian subcontinent, they had immense political and feudal access to many provinces. Taj Mahal is situated in the center of a large complex on 42 acres. The complex consists of the main tomb flanked by twin mosques—they are identical in size and rendition—that face the tomb. It also consists of a guest house and beautiful gardens called Chahar bagh, which used the Persian style.

Crenelated walls fence the entire complex, which opens in the south to move towards the north. A visitor first enters the forecourt or gate of red stone, which is an equally ornate and splendid specimen. Situated on the banks of the Yamuna River, the complex divides itself into four regions through channeled waterways. Although fenced, the fourth side opens to the river.

The Taj Mahal is built on a square and raised platform or a plinth. The tomb is the epitome of the Mughal architectural method called Hasht Behesht. Particularly, Hasht Behest is an idea of eight paradises, rendering the plan octagonally. Hence, the main structure of the tomb is set in a nine-fold plan, showing eight rooms surrounding the central chamber. The onion-shaped dome is flanked by four minarets at the four corners of the plinth. Mounted with a finial and a crescent moon, the dome is a golden spot of wonder. At the lower lever, four smaller-sized domes surrounding the central dome. Each smaller dome is comprised of a chhatri (kiosk), enclosing a balcony.

The arched gate to enter the tomb is called iwan. It is framed by a rectangular and decorated surface called pishtaq. The gates and other walls project chamfered corners, a peculiar style of Mughal architecture.

Remarkably, the four minarets are tilted away from the central dome, as a precautionary act to avoid damage to the main structure, especially during an occurrence of a natural calamity. Minarets also have a chhatri and a staircase to reach the top. They are associated with the religious duty of calling for daily prayers. The muezzin, the official assigned the announcing duty, calls the public for the namaz or prayer from these minarets.

The central chamber places the two cenotaphs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz. Shah Jahan died thirty years after his wife. Mumtaj died after giving birth to their 14th offspring in 1631. The real sarcophagi are safely stored at the lower level. The sarcophagi are ornate with calligraphy. The surface calligraphic verses from the Quran are inlaid in precious stones. The technique is known as Pietra dura, which uses cut and polished colored stones. The verses refer to the paradise and day of judgment, wherein God royally and dutifully rewards the faithful.

The tomb shows many floral patterns, as animal or human figures are prohibited, due to Islam protocols. In addition, the jali or a mesh decorative and lapidary is frequently observed.

Composed unconventionally, as opposed to other Mughal or Islamic tombs, the surface of the Taj Mahal is wondrously composed to derive an impeccable play of light and shadow.

Function

The Taj Mahal is a mausoleum and it serves a funerary function. Shah Jahan was the fifth Mughal king and had unrivaled authority over the Indian states. Despite having many wives, he was extremely fond of Mumtaj. Tormented by her sudden demise, he thought of building the most beautiful tomb for her. As opposed to black marble tombs in the Islamic culture, he demanded a white marble mausoleum.

The Mughals levied administrative power and their royalty had been fruitful in developing many architectural specimens. Among them, the Taj Mahal is the best work under the aegis of Shah Jahan. Owing to the despotic rule of Aurangzeb, their progeny, who had locked his father, Shah Jahan was unable to see the completion of the building. Hence, the Taj Mahal is a symbol of compassion and royalty.

As it is built on the raised platform, the concept refers to the royal status of the throne to god. Furthermore, it is an architectural metaphor for Paradise. Hence, the pools and gardens in the complex enhance the idea of paradise on the earth.

Most importantly, the Taj Mahal is the symbol of unconditioned love. Shah Jahan spent most of his time with Mumtaj, neglecting other wives. Though she was not interested, Shah Jahan confided many administrative and military decisions with her. One of the walls of the Taj Mahal has an inscription, which reveals praises for Mumtaz by Shah Jahan in the Thuluth script.

Significantly, the Taj Mahal emphasizes the power vested in royal Mughal patrons. Shah Jahan decided to build it in Agra due to many reasons. One of the reasons was the proximity of Rajasthan, a nearby state, and the vast resource of white marble for easy transportation. In addition, the building, enriched with Indian and Islamic principles, projects the idea of the greatness of Jahani rule. Technically, it glorified the Mughal rule.

Tradition

Taj Mahal epitomizes the unflinching expertise and power of the Mughal dynasty that invaded India in the 15th century. The first Mughal king, Babur, during his five years tenure, promoted art and culture, bringing many Persian artists to India. The lineage of promoting creativity was at its peak during the reign of Akbar, who promulgated the development of numerous ateliers. Many Indian, Persian, and Turkic artists were part of these ateliers. His son, Jehangir, and the fourth Mughal king was an enthusiastic promoter of miniature paintings. Similarly, Shah Jahan was also instrumental in maintaining the legacy of preserving and creating newer art forms, influencing and being influenced by indigenous Indian art. Some of the famous architectural buildings by Mughal kings include Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir, Fatehpur Sikri, Lahore fort, Buland Darwaza, Bibi ka Maqbara, among many others.

With Taj Mahal’s accomplishment, the Mughal architecture cleverly portrays a synthesized merger of Islamic and Indian architecture. Glorifying his dynasty, Shah Jahan posited the Taj Mahal as a propagandist monument to eulogize self-rule. Many motifs from Hindu culture had been incorporated to present a harmonious acceptance of India’s diversity. While the onion dome denotes Islamic style, some plant motifs, and white marble are typically Indian.

Patrons

Mughals were Islamic rulers in India – known for extravagance, art patronage, and despotic encroachment of Indian provinces. It is mentioned that Shah Jahan had already thought of building a Taj Mahal irrespective of Mumtaj’s untimely demise. Generally, Sunni Muslims favor a simple burial under an open sky but the Taj Mahal was an exception, among the other few domed mausoleums. Situated on the bank of the Yamuna River, which allowed for easy access to water, Agra was known as a “riverfront” city.

The plans for the complex have been attributed to various architects of the period, though the chief architect was probably Ustad Aḥmad Lahawrī, an Indian of Persian descent.

The five principal elements of the complex, which includes the main gateway, garden, mosque, jawāb (literally “answer”, a building mirroring the mosque), and mausoleum (including its four minarets) were conceived and designed as a unified entity according to the tenets of Mughal building practice, which allowed no subsequent addition or alteration.

The building commenced about 1632. More than 20,000 workers were employed from India, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and Europe to complete the mausoleum itself by about 1638–39. The adjunct buildings were finished by 1643, and decoration work continued until at least 1647. In total, the construction of the 42-acre (17-hectare) complex spanned 22 years.

Setting

Taj Mahal welcomes millions of worldwide tourists every year. After the Taj Mahal was listed a one of the seven man-made wonders of the world, its popularity has grown by leaps and bounds. This Mughal mausoleum has also been a hotbed of political and cultural concerns. This has resulted in many new rules and regulations for visitors. Shah Jahan erected this wonderful tomb as a token of limitless affection. This was a ground-breaking achievement. It has continued to draw crowds to Agra to receive a glimpse of architectural beauty. Even after four hundred years Taj Mahal continues to inspire great awe.

During this time in history, the Indian continent observed an influx of Portuguese, Dutch, and British traders, conducting business with Indian counterparts. The presence of Europeans also appears in many Mughal paintings, proving their acceptance in Mughal courts. Shah Jahan was a promoter of arts and culture. This did not pass onto the next Mughal ruler and his son Aurangzeb. This led to the fall of the Mughal empire, leaving ground for the British to take charge by the 18th century.

UP NEXT:

South, East and Southeast Asia

300 BCE-1980 CE

TOPIC 8.4 Theories and Interpretations of South, East, and Southeast Asian Art